In a world where tool companies race each other to develop the best battery technology and offer the largest selection of cordless tools, it’s easy to forget that for most of human history, all tools were cordless.

Granted, I furnish the carpenters that work on my projects with power tools (both corded and cordless), and those tools have an important place in a modern commercial carpentry operation. But there is something civilized in the relative peace and quiet that comes with hand-tool use. For me, nothing epitomizes the downright pleasant difference between electric power tools and hand tools the way a mitre box does.

It seems these days that the mitre saw is the measure of the carpenter: it’s usually at the centre of any jobsite setup. It may be the most important power tool a finish carpenter owns, and the major tool manufacturers know it. Models range anywhere from under two hundred dollars for cheaply made saws aimed at the DIY market, to heavy duty, large capacity models that can run about a thousand dollars, and right on up to deluxe, highly accurate models complete with high-end dust collection that will run you well into the thousands

I’ve spent a lot of my live behind the trigger of a mitre saw, so I feel like I’m particularly qualified to say that the noise and dust of a mitre saw can be intense. (As an aside, I would like to repeat a piece of advice I often give new carpenters: when you put on your PPE, it’s very easy to neglect hearing protection, because, for the most part, the damage done to your hearing by loud machines takes years to manifest itself. Wear your hearing protection. I wish someone would have told me that when I was starting out.)

When my daughter was born, I started looking for ways I could make my shop child-friendly, and the mitre box seemed like a perfect solution. No more loud noises, no more clouds of airborne sawdust, a place where we could hear each other or listen to music in comfort. I set about hunting in antique stores and fine tool manufacturers. I originally purchased a pretty decent mitre box from Lee Valley Tools, but when I stumbled across a Stanley 358, I snapped it up.

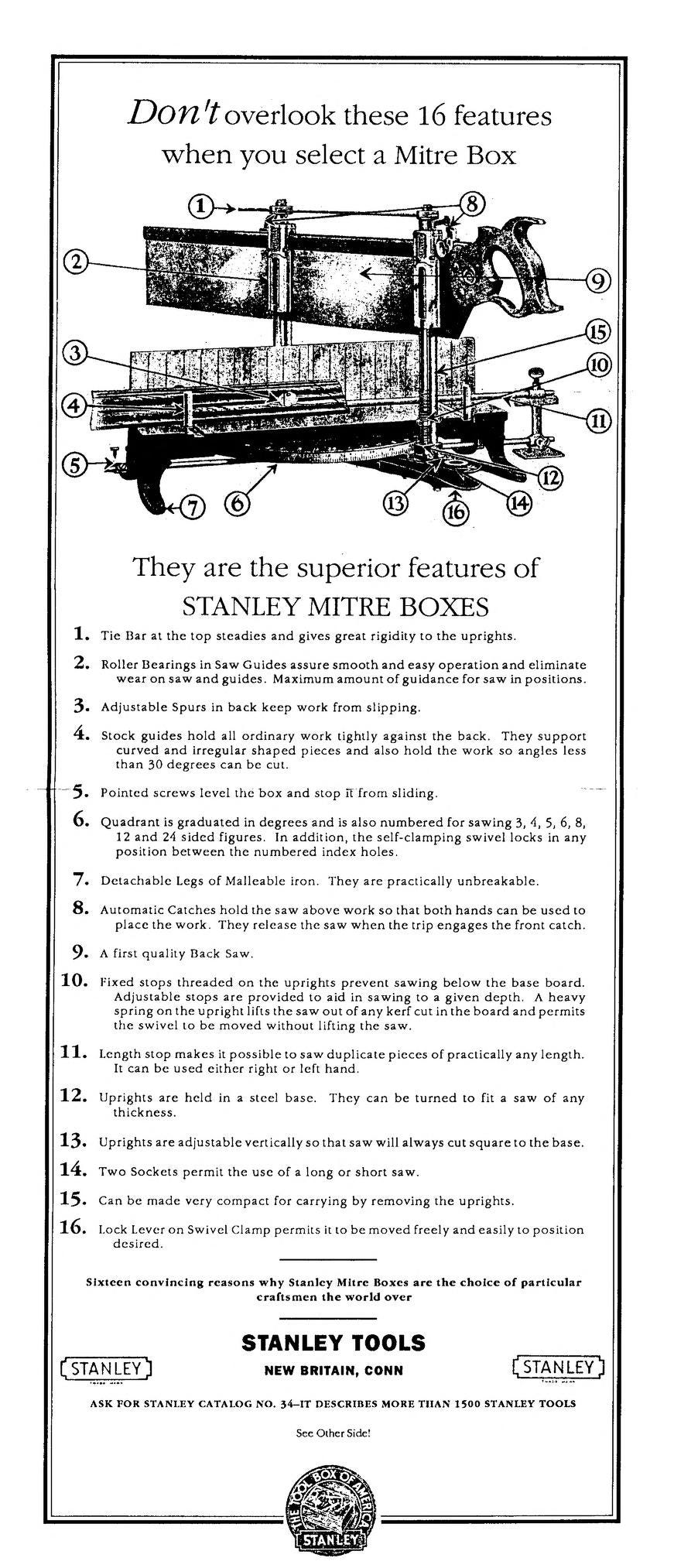

Stanley Mitre Boxes

Stanley produced it’s first mitre box in the late 1800’s, and continues manufacturing them to the present day. Today’s versions are mostly plastic and of very poor quality, but the models throughout the 19th and much of the 20th centuries were wonderfully made, accurate and durable. They hit all price points, catering to DIY enthusiasts with cheaper and smaller models, and furnishing the professional market with some excellent offerings, many of which are now prized by collectors and users alike.

The Stanley 358

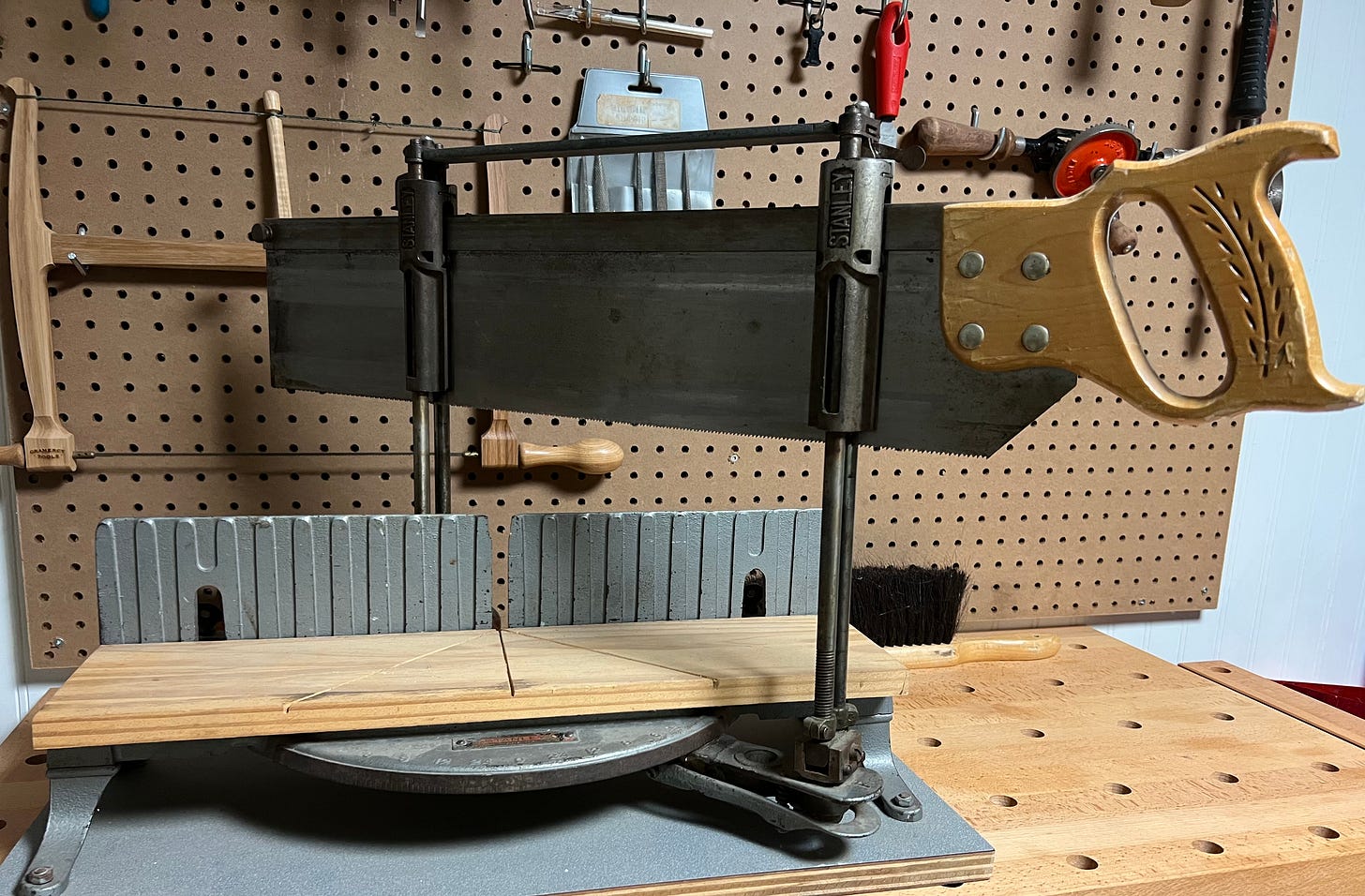

Among the most desired mitre boxes is the Stanley Miter Box No. 358. It has a relatively large capacity (I can just barely cut 2x10’s at 90° and 2x8’s at 45°). It is quite durable, featuring a cast iron base with jappanning and sturdy steel moving parts. It originally shipped with stock guides and length stops, but as is often the case, mine did not have them when I found it in an antique shop. (If I can’t find replacements, I may consider manufacturing my own, as I stumbled across this wonderful restoration by Brendan Dahl in the course of writing this article).

The quadrant, or protractor, is fairly interesting if you’re used to modern mitre saws. Where we normally see measurements in degrees, and detents (or stops) at important numbers such as 45° and 22.5°, the 358 has a series of numbers and corresponding detents. At 90° the detent is labelled 0, and from there there are detents labelled 24, 12, 8, 6, 5, and finally 4, which occurs at 45°. The key to understanding these numbers is that they represent the number of sides a figure you could create by cutting pieces at that angle. So, if you cut workpieces at the number 4 detent (45°) you could make a four-sided figure. If you were to cut pieces using the number 6 detent, you could make a six-sided figure, meaning that the number 6 detent is 30°. It’s a system that takes a little getting used to and was likely a function of the types and styles of trim that were common when the mitre box was developed

.

Stanley made the 358 from 1905 through to 1972. Mine was made in Canada, which I find interesting; I haven’t found much literature online regarding Canadian-made mitre boxes from Stanley. Two models were made, the regular cast iron 358, which I have, and the 358A which was made out of aluminum. The aluminum version would be much lighter which would be a significant advantage for a site carpenter.

The 358’s Place In My Shop

In my current home, I have a basement shop. It’s across the hall from the office I’m sitting in right now. I don’t live in a large home, and so I opted to keep all of my woodworking machinery in the garage, for rough work, and to keep the basement shop for hand-tools only. That keeps the noise and dust separate from our living areas. In my last home, the machinery and the hand-tools occupied a larger shop together.

Before I separated my hand-tool and machine shops, I didn’t give the 358 the attention it deserved. Out of habit, I often just took the workpiece to the corded mitre saw. Now though, when faced with the option of taking a workpiece upstairs and outside to the garage, in the depths of Canadian winter, or using my 358 which is right behind my workbench in the warmth of my basement shop, the choice to use the mitre box is usually a very easy one.